Fishbone/Ishikawa: Analytical Frameworks Pt.2

Jan 2026

In my last post in this series on Analytical Frameworks, I discussed the Project Premortem. The Premortem is future-oriented; participants imagine they can see into the future and obtain certain knowledge that their project has failed.

The Fishbone/Ishikawa diagram, on the other hand, dissects problems past and present by tracing them back to their origins.

The diagram was developed by Japanese engineer Kaoru Ishikawa at Kawasaki Steel Works in 1943. It was designed to address quality control issues in steel manufacturing plants. Originally named after its creator, it came to be known as the Fishbone Diagram because the diagram has the shape of a fish skeleton.

While the Premortem is proactive, the Fishbone Diagram is reactive. It forces structured causal mapping of a problem into predetermined categories. The tool’s widespread adoption is likely due to its exemplification of several cognitive principles: visual processing, externalizing thinking, and systematic categorization.

How it Works

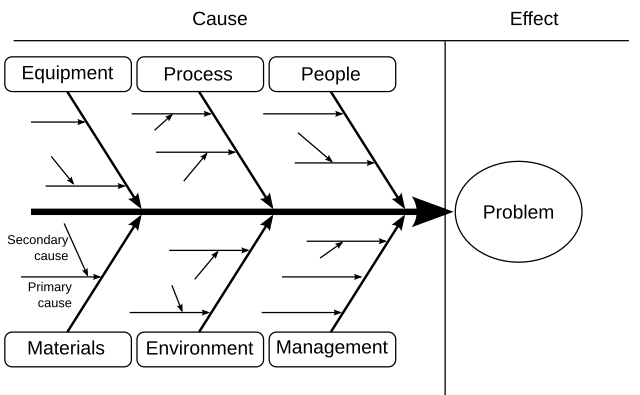

The “head” contains a well-defined problem statement, like: “A decline in both discovery and reach for non-viral content on X.”

This is the effect you are analyzing for causality. In the cause section, where the “bones” lie, you place your chosen categories and begin mapping primary and secondary causes to each of them.

Popular models for the predetermined categorization include:

6M model — Manpower, Method, Machine, Material, Measurement, and Milieu/Mother Nature.

8P model — Product, Price, Place, Promotion, People, Process, Physical Evidence, and Productivity.

4S model — Surroundings, Suppliers, Systems, Skills.

You can also choose custom categories, as long as they are sufficiently systematizing for your problem statement. The fishbone diagram figure at the top of this section uses categories outside of the typical models.

For the problem of my X discovery/reach, I might choose: System/Incentives, Content, User Behavior, Network, External Context.

The facilitation process for filling out the diagram usually includes a cross-functional team of 5-8 people with firsthand knowledge of the systems involved. The steps are:

-

10-15 minutes documenting the problem and crafting the statement.

-

30-45 minute period of silent brainstorming followed up by a round-robin share-out from participants.

-

After a short break, 15-20 minutes asking “why does this happen?” for each primary cause, to generate secondary causes. The 5 Whys Technique involves following up every answer to “Why?” with another “Why?” up to five times.

-

“Multi-voting” at the end to determine which suspected causes to prioritize and validate with data or experimentation.

What I like about this tool compared to the Project Premortem is that it can be done solo. Working out a problem like this is probably better in a group because you’ll get more breadth of experience and opinion, but it’s still totally possible to go it alone to a) craft a problem statement, b) brainstorm primary causes for predetermined categories, and c) “why down” the primary causes into secondary causes.

Why it Works

Advantages of the fishbone diagram include:

Narrows the scope of an investigation to be more manageable or actionable.

Generates possible causes that we can act on.

Effective use of time and resources.

Visualizes the relationships between all possible causes for a focused problem.

Establishes a shared understanding of the possible causes and solutions.

Enables logical discussion of the next steps for testing changes.

Documents which causes are targeted for data collection or have already been verified with data.¹

The forced categorization prevents “premature closure” — you don’t get stuck on the first cause that comes to mind, and you’re forced to think of causes across multiple areas.

Problems/Limitations

Getting symptoms confused with root causes is a likely issue, which is what the 5 Whys Technique is meant to solve.

Another limitation is that the process generates possibilities, but they’re not validated. That’s why the group must select potential causes to go on to validate. To actually do something with this tool, you need either further investigation of the data, or iteration of processes relevant to the causes to see if they improve/solve the problem.

Other potential issues: poor problem definition, groupthink, sprawling sessions. As with the Premortem, the value of the session relies on good facilitation.

Using it Solo

If you’re working out a problem for yourself with a fishbone diagram, I think the most useful part about it is the structure it provides.

You can also “roleplay” different perspectives, as if you were a team of stakeholders, to try to generate the variety of answers you’d get from a group session.

Working with LLMs with persona prompting could be another way to get diverse causes. Just don’t forget the 5 Whys Technique, because “why-ing it down” can make up for some of the limitations of working out this process alone.

If you try this on a problem of your own, I’d be curious what categories you landed on. Let me know via comments.

In my next post in this series, I’ll be looking at MECE — this uses the concepts of “mutually exclusive” (two events cannot occur simultaneously) and “collectively exhaustive” (the set of ideas includes all possible options) for problem-solving.

So Long,

Marianne

¹

Kumah, A., Nwogu, C. N., Issah, A.-R., Obot, E., Kanamitie, D. T., Sifa, J. S., & Aidoo, L. A. (2024). Cause-and-effect (fishbone) diagram: A tool for generating and organizing quality improvement ideas. Global Journal on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 7(2), 85–87. https://doi.org/10.36401/JQSH-23-42