Project Premortem: Analytical Frameworks Series

Jan 2026

“You’re gazing into a crystal ball that can show you the future of your most cherished project. Bad news: it’s an abject failure.”

Dear Friends,

For inkuary, I’m writing through two series: one on Analytical Frameworks and Tools, and the other an Intro to Computational Semiotics.

This post is the first part of the former, and this first “framework” is more like a structured exercise:

The Project Premortem

Some variation of the above “crystal ball scenario” is how the premortem begins. A facilitator, usually the project lead, asks participants to imagine that they have magically received advanced knowledge that their project is a failure — totally, and with absolute certainty.

With this foresight, can they come up with the probable causes of the failure?

It was developed by cognitive psychologist Gary Klein¹ as a risk assessment tool, and it’s the inverse of the typical project postmortem. Instead of looking at the project in hindsight and asking what happened/what could have been done better, the premortem takes place before the project even begins. It asks the team to assume spectacular failure, then work backward from that assumption to arrive at the causes.

It’s effective because it provides structure for project teams and stakeholders to overcome groupthink and a fear of repercussions for providing critique. They’re given explicit social permission to surface concerns that might have otherwise gone unspoken.

First I’ll explain how it works, then a few reasons why it works. I’ll also draw some connections to my own projects and creative community.

Five Steps for a Project Premortem

-

The facilitator gives the team a project briefing, ensuring everyone is at the same level of familiarity with the proposed plan.

-

Introducing the “crystal ball” scenario, he asks the team to imagine that they have foreknowledge that the plan has completely failed.

-

The participants take 3-5 minutes to silently, independently generate reasons for the failure — especially reasons they would ordinarily be hesitant to bring up.

-

Round-robin and one at a time, participants share the reasons they came up with. The facilitator should go first, to model the necessary candor.

-

After consolidating the reasons, the team revisits the plan: they generate a robust risk register and mitigation plan based on the premortem exercise.

Note: it’s the future-temporal register and the certainty of the failure that make the premortem work.²

If you only ask the team to think about “what might possibly go wrong,” they’ll provide abstract speculation — probably tepid, vague intimations. When the frame is that this project has certainly and spectacularly failed, and they are explicitly encouraged to share all possible causes, it activates much more concrete reasoning. It also helps participants overcome the fear of being “impolitic.”

Some teams with challenging hierarchical organization and internal politics might also allow for anonymous submissions during step four³, so that team members can feel comfortable raising particularly sensitive concerns.

The efficacy of the premortem compared to other techniques has some empirical basis. In How to catch a black swan: Measuring the benefits of the premortem technique for risk identification, Gallop, Willy, and Bischoff conclude that “teams using the premortem technique identified better quality risks, more quality changes to the plan, and identified more black swan risks than their brainstorming counterparts.”⁴

I’m seeing three major factors that make the premortem work:

-

Prospective hindsight, which activates experiential knowledge/world modeling.

-

Social permission, which comes from the exercise structure + the facilitator modeling the desired candor.

-

Collective intelligence aggregation, which results in risk assessment greater than any one individual could produce on their own.

I’d like to stress this third factor — collective intelligence.

Many of you, like me, are currently working on independent creative projects. I’ve never done a premortem, but based on my research, I don’t think it could be too effective as a one-man exercise.

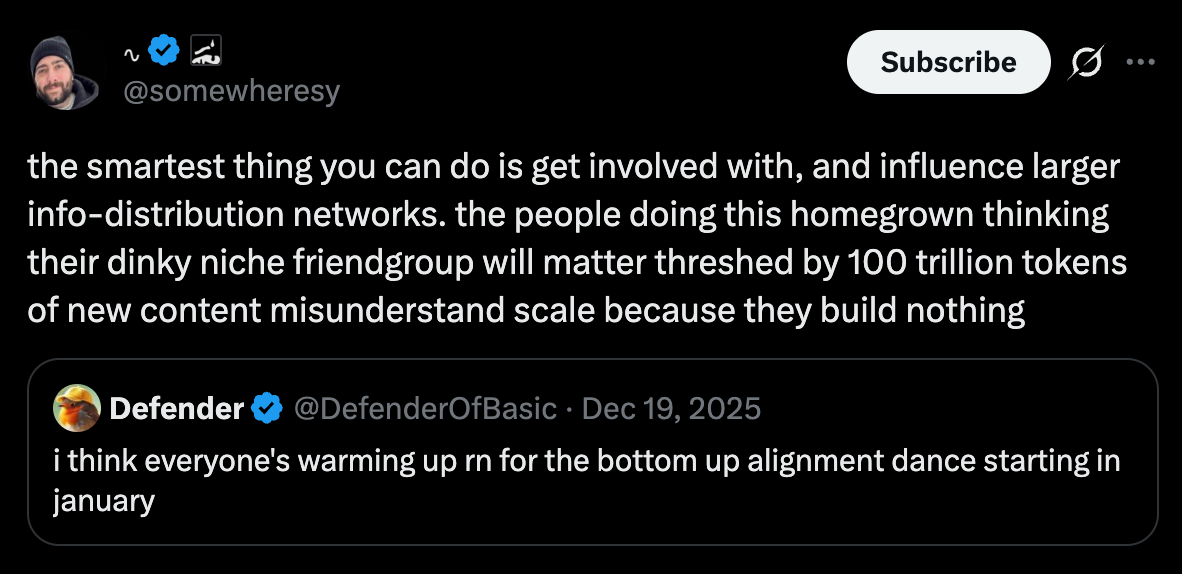

So I’ll close by highlighting the opportunity: we solo artists/creators/builders could form communities of critique around techniques like this, where we provide mutual benefit by participating in e.g. premortems for each others’ projects.

If you’re interested, I’ve got protected time each week for group work/online community, and I’d quite like to test this one with others.

Ideally this will surface more opportunities for us to work together, too, because:

So Long,

Marianne

This was part one of a 7-part series. I’ll be alternating between this Analytical Frameworks series and the Computational Semiotics series over the course of the month. The next framework is: Fishbone / Ishikawa Diagram.

¹

Klein, G. (2007). "Performing a Project Premortem." Harvard Business Review, 85(9), 18-19.

²

Mitchell, D.J., Russo, J.E., & Pennington, N. (1989). “Back to the future: Temporal perspective in the explanation of events.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 2(1), 25-38.

³

Serrat, O. (2017). "The Premortem Technique." In Knowledge Solutions (pp. 189-193). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9_22

⁴

Gallop, D., Willy, C., & Bischoff, J. (2016). “How to catch a black swan: Measuring the benefits of the premortem technique for risk identification.” Journal of Enterprise Transformation, 6(2), 87-106.